If one was to pen a business plan for racing, it would have one action plan

- When things go wrong in racing’s ship – put the prices up on the bookmakers

Racing, and racetracks don’t seriously consider actually improving the product. They don’t look at days like Super Saturday and decide it needs trimming for effectiveness. They will schedule a race to go off ten minutes after the Grand National, and cut to it by contract stipulation. They put on extra days on racing festivals and fill them with handicaps. Or split championship events like the Cheltenham Gold Cup and the Champion Hurdle. The regulator is ruled by the will of the tracks for wall to wall racing, and cheap black type, and shows no appetite for real change

As a career bookmaker, I’ve always known, whilst not accepting, that racing as a product is disproportionately expensive. I require a much higher margin to absorb exorbitant streaming charges, levy, duty and marketing of the same. Racing does represent a far higher share of my customers interest. That won’t be true of the likes of 365 however, where racing might attract just ten percent of the giants product turnover.

Is it any wonder, therefore, when racetracks like Arena hike their streaming charges up by circa 20 percent, that the likes of Flutter simply say no. Arena was already expensive, for a product that several days a week might have little or no product to display. Bookmakers need content, and they need it to be compete favourably with Man Utd vs Man City. Arena, however, isn’t profitable. To that end I understand the money quest- but you can’t just put the prices up to make yourself look more attractive on the market.

In similar vein racing ‘expects’ a greater levy share. Levy is simply another ‘tax’ bookmakers pay. Racing wants more levy to fund its offerings at a time when the amount of betting on sports in 2024 declined by 9 billion pounds! Exacerbated by highly restrictive business practices such as ‘affordability checks’ which have seen many high end players simply depart the UK market

Let us be clear- affordability checks aren’t the fault of racing. It is policy which emanated from an over zealous gambling commission, embarked on a ‘public health’ mission, rather than acting as the gambling regulator. Racing and racetracks have fought these checks almost isolated. Few bookmakers have publicly said anything. Certainly not the major bookmakers, and their marketing arm, the ‘Betting And Gaming Council.’ Who have publicly supported affordability, rather than challenge deeply unpopular policy. To be fair the BGC has a outstanding record in fail.

Leading the fight, in a leadership vacuum only Racing can create (no CEO for 2 years?) has been Martin Crudace. A smart cookie who heads Arena Racetracks. He’s been an immovable object in the path of gambling reformers. His powerful, persuasive, argument is simple. Affordability checks haven’t reduced the (already world wide low) level of problem gambling by one person. They don’t work. A stance the gambling commission now accepts, but won’t admit (their involvement)

Opposing gambling in pretty much all of its forms is Derek Webb. Webb invented the casino game ‘3 card poker’ – a voracious product so profitable to casinos it often fronts the house. Gambling made him a very wealthy boy, and he sees no irony that he is now using all the money he earned from a highly lucrative casino game into anti activism. Chucking out millions to impose his new morals on the industry. For example funding the opposing candidate to Philip Davies at the last election. Paying for loaded ‘survation’ surveys and other research specifically designed to portray gambling as somehow dirty. He doesn’t accept people’s right to choose. To bet at whatever level they prefer, and under their own controls. Nor their right to the privacy of their data, with demands for affordability and ‘single customer view’ access to people’s finances.

Yet he now appears to have untangled racing from sports betting and by all accounts the SMF (which Webb funds) is working with racing

Also at the altar of sponsored opinions are activists against gambling- like James Noyes. He is a left wing academic, funded by Las Vegas philanthropist Derek Webb. In 2020 Noyes argued passionately, without a shred of evidence, that affordability should be implemented at levels as low as £23 of customer deposits a month. It was an absurd and irrational argument, especially given the clear opposition to such plans from punters. In the last year alone, sports betting has declined by some 9 billion pounds, and hasn’t saved a single individual from harm. Noyes now describes affordability as a ‘fiasco’ yet he drove the policy irresponsibly. He now wants Racing to commit to his new plan- to split horseracing out from all other betting products. Notably sports.

However, he has now managed the conjuring trick of convincing Crudace in the new ‘Axe The Tax’ campaign that racing should speak only for itself. It is a smart move, one would have thought noone would countenance. Noyes, and his benefactor Webb, appreciate that with Crudace and Racing out the way, they can advance their cause to establish gambling, and notably sports betting as a health emergency (The words of Noyes). The removal of horse racing objections representing a major step in SMF ambitions to raise gambling taxes to prohibitive levels, and the acceptance of sports betting as a harmful product. We have even hear Zarb-Cousin argue on the Luck show that horse racing represents less of a welfare issue than greyhounds. Who is he kidding?

The SMF appear to be running the show. They will both, of course, claim that they are not anti gambling, but when you advocate restrictions on gamblers and their activities, sponsorship of gambling, huge tax rises, advocation of affordability checks at absurdly low levels, and prohibitive practices which you absolutely know can only send consumers to the black market? You’re a prohibitionist, you just don’t like being called one.

What is the issue with ‘splitting out’ racing? Well it is exactly like advocating in a supermarket, that the milk, tea and eggs be treated as ‘favourable products.’ The argument is racing to be afforded a low duty rate, and the decrease in duty made up by a commensurate increase in levy! In exchange, racing will ‘stand aside’ from any involvement in the rest of the sports betting package bookmakers sell. This ‘splitting out’ of racing, notably excludes greyhound racing from any tax break. An astonishing position! Thrown to the dogs, as they say?

Aveek Bhattacharya, the Social Market Foundation man at the treasury, was formerly funded by Webb at the SMF, has somehow managed to have himself installed as the head of excise at the treasury. A policy position of incredible influence. The fact that Webb funds the Labour party of late to the tune of 1.5 million raises the more than reasonable speculation of cash for favours. You’re allowed to donate to political parties, but you’re not supposed to expect ‘treats.’ We all accept that to be nonsense. But the relationship with Bhattacharya, the SMF and Webb is undisputed. Webb is playing his orchestra with far more skill than those representing racing and betting, and Noyes believes he can smooch everyone onside, with a campaign of reasonable appeasement.

Bhattacharya, advocates that betting duties be ‘harmonised.’ In said regard his views are aligned with several student politic standard position papers opposing anything humans like to enjoy he has penned in the past. Like smoking, drinking, and of course gambling. He is no friend of anything humans consider enjoyable pastime. The suggestion is sports betting be raised to 21% – the current rate of remote gaming. Racing wants its own level set at 10%. And the difference made up by an appropriate increase in levy. I hope you’re following this?

Well, if this treasury official gets his way, sports betting will be hiked by 40%. Racing thinks it will be exempt, and there’s a more than fair chance that’s precisely what will happen. Since it is a heritage sport all would want to survive. The callous advocation by racing, and the tracks, a form of cognative dissonance, that it should all be about them, leaves bookmakers shouldering a huge duty increase. And potentially levy too.

The trouble with this is how bookmakers operate. A shop, or online firm, that offers racing, offers that product as an element of various sports. Without football for example, no betting shop would be viable. Nor any online business for that matter!

So why such a naïve stance?

Well it is difficult to understand such folly. Racing must believe the unsupportable tax hike in sports betting will simply be absorbed by the 4 largest companies. They calculate the loss of the independent market as a ‘price worth paying.’ No independent can withstand such a rise in tax. And to pass the duty cost on by delivering higher margin, or by removal of offers, like best odds guarantees, robs bookmakers of any competitive advantage against the black market- who pay a zero rate of tax and levy!

It follows the racing alliance believes big corporations, like the 35 billion pound Flutter should ‘just pay.’ Because it can afford to. Racing has deep history with such views. Even if racing is a loss leader to the gaming companies.

It is a bold plan. One born of the beer mat and the incredibly smart Derek Webb, who has managed to split the immovable racing out. Flutter, for example are already saying no to hikes in streaming and levy. Quite why racing thinks it can ‘bully’ such companies into ‘just paying?’ Well that goes back to rule number 1. Which I repeat

- Bookmakers should just pay.

The future

If racing gets its way, it must believe the ‘split out’ can last ad infinitum. In reality those who oppose gambling on moral grounds, and horse racing on welfare, will be unrelenting in their opposition to racing being treated as a special case- when it causes so much (imagined) harm. Racing will end up ‘harmonised.’ The independent bookmaker market (that’s companies like Geoff Banks Online, Star Sports, Fitzdares etc) will disappear offshore. Acceptable collateral I believe that’s called. Finally racing thinks government will be able to bully Flutter, Entain, Evoke and 365 into a new world of 40 percent uplifts in tax and levy. Play stupid games- win stupid prizes

If I was the CEO of Flutter, or Entain, and racing wins the round in securing for itself more levy, whilst turning its back on its association with sports? Well I would find I have two products ‘harmonised’ for tax at the same high rate. There’s no tax advantage now to offer racing. One is my gaming with minimal cost attaching – the other is the racing, which is enormously expensive in charges to offer. Which part of my business would I be shoving down my customer’s throat? Inevitably it would be Racing that would suffer. And I wouldn’t lose a moments sleep about a sport that abandoned its defence of the other products which effectively offer punters a ‘one stop’ solution for their betting. Racing, having given the treasury the nod for huge tax increases in sport, has committed the biggest single act of immolation in its history.

Good luck to all those of you who think you can manage such a trick on companies domiciled in Gibraltar and Malta, I have said it before, but I will repeat. Racing has to look to itself and modernise. Punters? Well your future lies offshore. And as offshore entities like Stake prove they can pay winners – they will dominate the market. That’s if Flutter, 365, Evoke and Entain don’t set their shop up in Malta for good, and put two fingers up to racing, and this government.

Who could blame them?

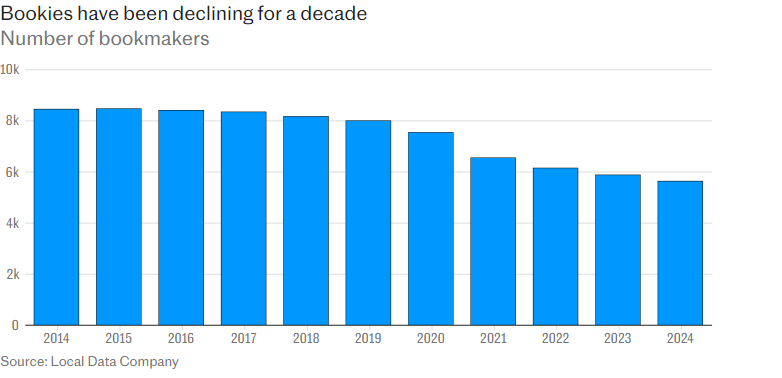

However, three long-term consumer demand trends are much more sticky than channel shift.

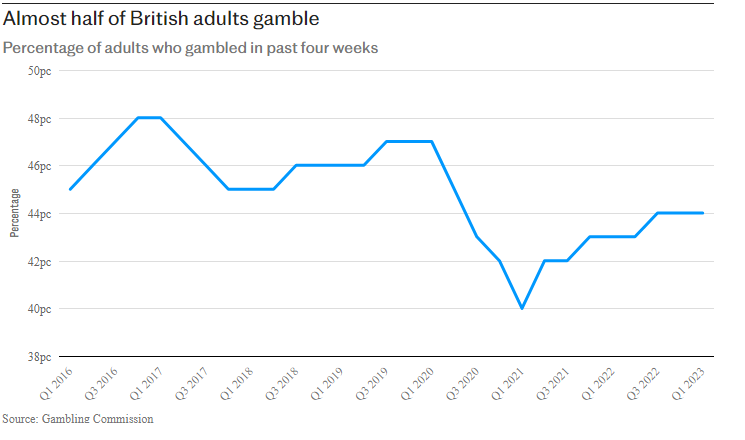

However, three long-term consumer demand trends are much more sticky than channel shift. The relative growth in slots has therefore partially mitigated the relative decline of National Lottery revenue to keep gambling expenditure as a proportion of Household Disposable Income relatively stable at c. 1% over 25 years (note, FY9 was low because of the implementation of the Smoking Ban, the loss of S16/21 machines, and the onset of a global recession). However, an underlying decline can be detected and if the National Lottery is not turned around then it is likely to become more visible, in our view.

The relative growth in slots has therefore partially mitigated the relative decline of National Lottery revenue to keep gambling expenditure as a proportion of Household Disposable Income relatively stable at c. 1% over 25 years (note, FY9 was low because of the implementation of the Smoking Ban, the loss of S16/21 machines, and the onset of a global recession). However, an underlying decline can be detected and if the National Lottery is not turned around then it is likely to become more visible, in our view. For all the hype about a changing landscape, very little is changing in terms of underlying consumer behaviour other than channel shift. British consumers are, if anything, gambling less, albeit with revenue concentrated in a smaller number of participants.

For all the hype about a changing landscape, very little is changing in terms of underlying consumer behaviour other than channel shift. British consumers are, if anything, gambling less, albeit with revenue concentrated in a smaller number of participants.